Moving away from classic Y shaped full-length antibodies: Why so many formats?

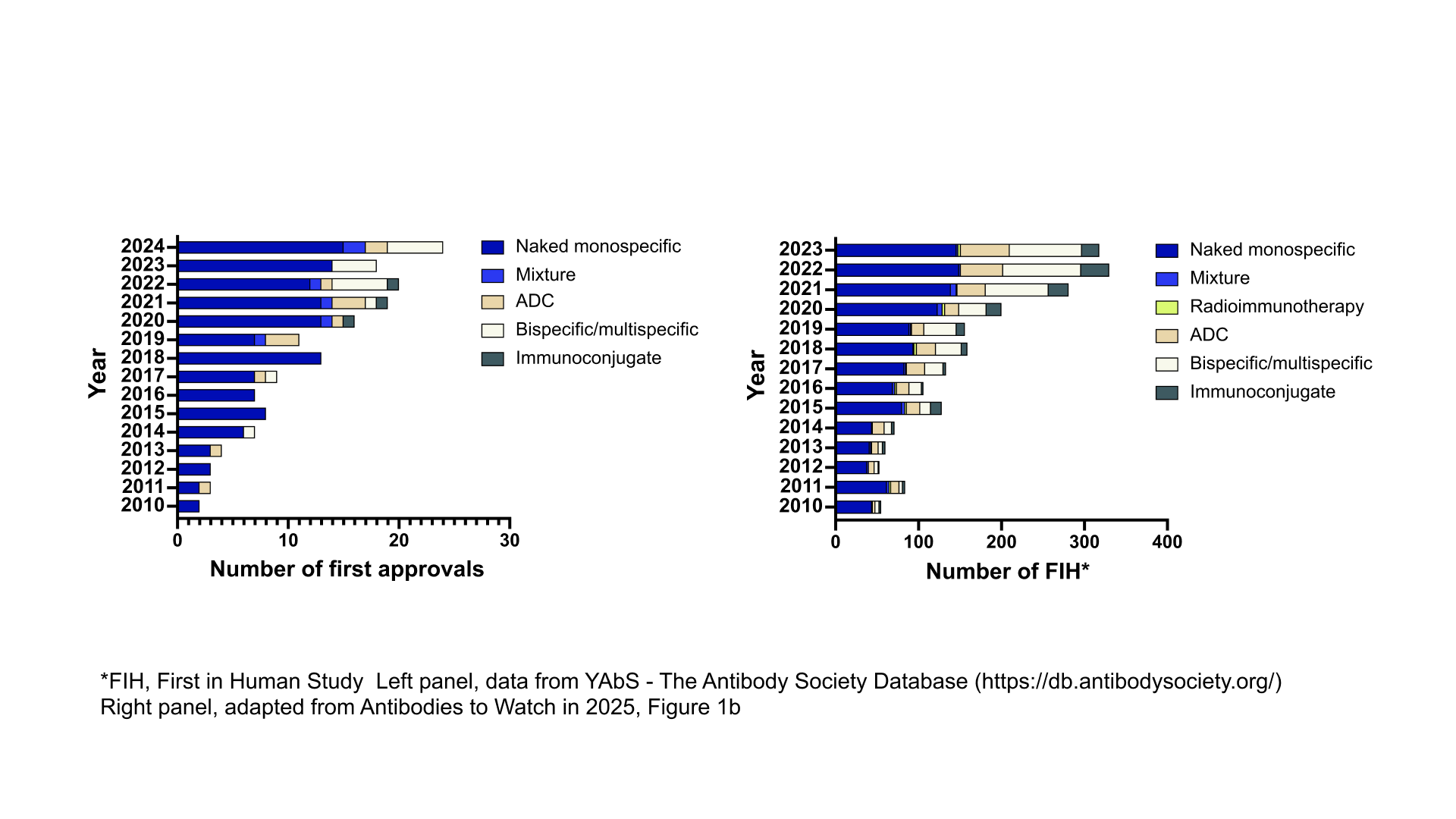

In the past decade, there has been a substantial increase of antibody therapeutics with unconventional format entering the clinic, reaching late-stage studies, and being granted marketing approval.1,2,3 Since 2021, non-canonical antibodies (e.g. bispecifics, multispecifics, antibody drug conjugates and immunoconjugates) account for nearly half of the antibodies entering first in human studies, and a third of those being granted marketing approval each year.3

Several factors contributed to the increased diversity of antibody therapeutic formats.

Advances in structural biology and antibody engineering have enabled scientists to design therapeutic antibodies as modular systems. Functional elements can now be combined into antibody fragments (with or without Fc), appended immunoglobulins, or antibody fusion proteins, to generate monospecific or multispecific antibody formats tailored to fine-tune valency, specificity, biodistribution, and function.

These ad hoc designed antibody formats, tailored to achieve the desired biological properties, have been crucial for overcoming the limitations of traditional antibodies and for expanding the range of therapeutic applications.

Finally, the growing number of biotech and pharmaceutical companies developing antibody therapeutics, together with considerations around Freedom to Operate (FTO) and Intellectual Property (IP), has further driven the development of novel antibody formats.

Why we need a universal nomenclature for antibody therapeutics

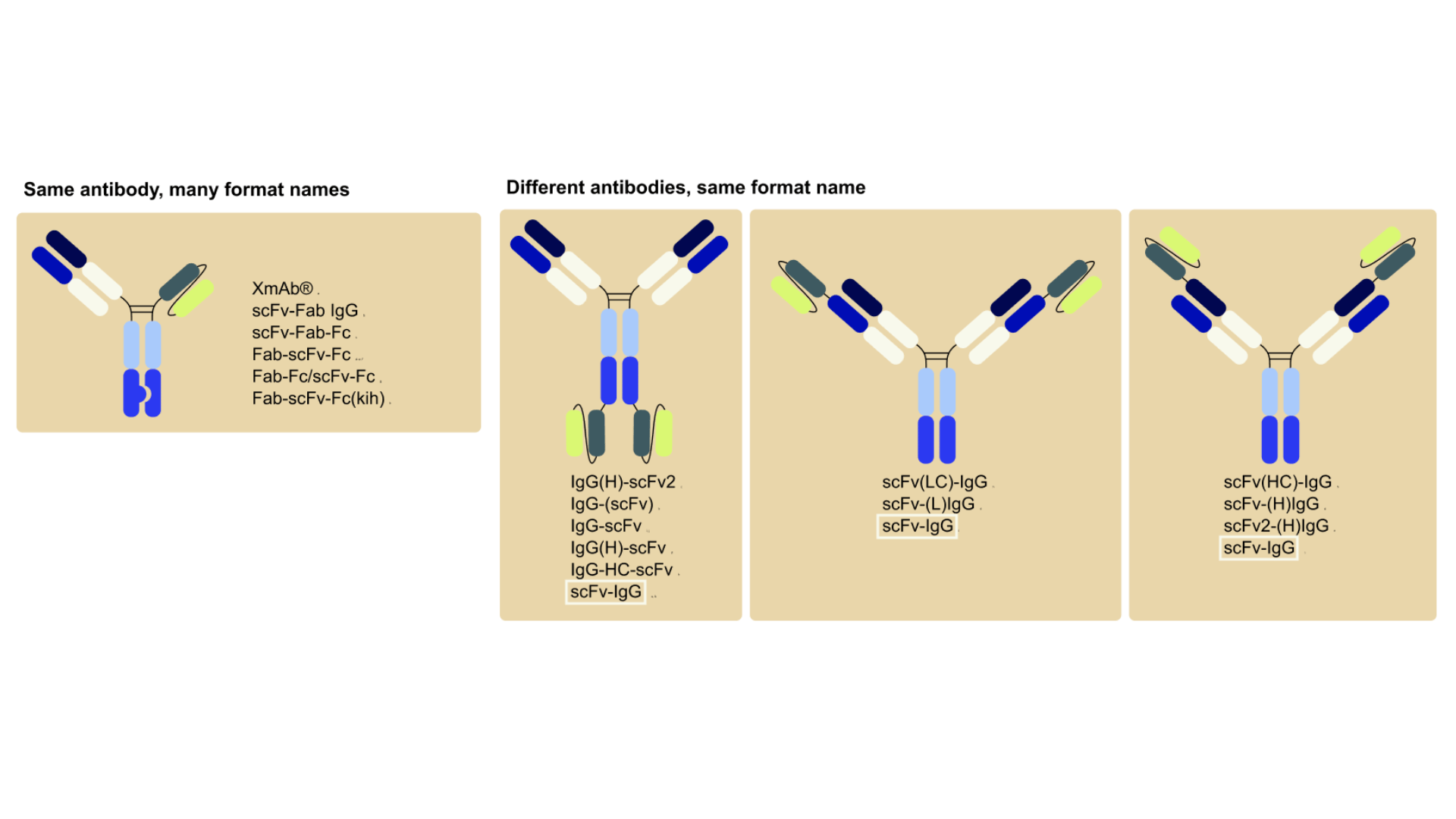

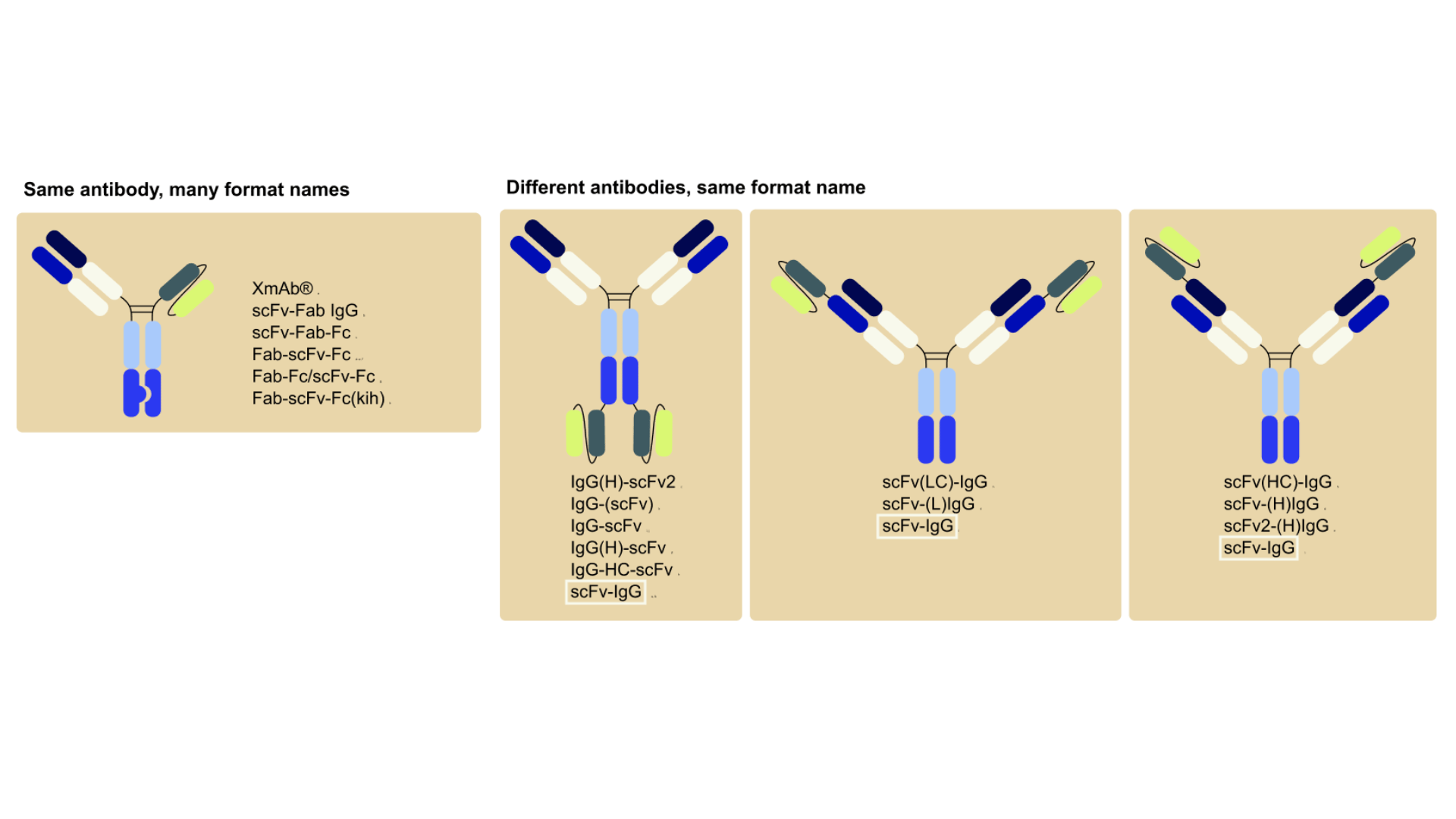

Currently, antibody-based formats are often referred to by names coined by their inventors, some of which are trademarks (e.g. BiTE, DART, Nanobody, CrossMab) often with no universal logic or structure information, while others (e.g. scFv-Fc, Fab-IgG, scFv2-Fc, VHH2-Fc) are often inconsistent and can vary even across labs or companies. As a result, understanding what a name actually means often requires digging through papers or patent filings, slowing down communication, collaboration, and discovery.

This lack of standardization not only affects scientific communication, but also complicates the annotation of antibody-related databases. Different databases use different strategies to describe formats, and in many cases, molecules are annotated using the names provided by their developers or using one of the various synonyms used in the literature to describe the molecule.

The consequences extend beyond databases: inconsistent or vague naming also hinders clarity in patent literature, INN submissions, and regulatory filings, where precise format descriptions are critical. Without a standardized nomenclature, it becomes difficult to reliably compare formats, track design innovations, or assess therapeutic equivalence across sources.

As we enter the era of machine learning and AI-driven antibody research, resources such as antibody databases, patent literature, regulatory documents, and prescription labels hold valuable information. However, without standardized terminology, extracting and integrating this data becomes a major challenge. This inconsistency limits the generation of structured and harmonized datasets which are a critical prerequisite for applying machine learning to antibody discovery, developability analysis, and format optimization.

A standardized antibody format nomenclature will:

- Enable clearer scientific discussion

- Save time by eliminating the need to research background details for each format

- Streamline formal processes like patent filings, regulatory and INN applications

- Support project continuity and data integrity across research teams

- Improve the consistency and usability of antibody databases

- Allow meaningful comparisons between formats, facilitating formats grouping for computational analyses, including machine learning

Existing Classification and Emerging Nomenclature Systems

Several groups have recognized the growing complexity of antibody formats and proposed ways to classify or name them more systematically.

In 2017, Brinkmann and Kontermann presented the “zoo of bispecific antibody formats” with over 100 different formats.4 They represent bispecifics and multispecifics as modular molecules assembled using a toolbox comprising different building blocks (antigen-binding modules as well as homo- and heterodimerization modules). They classify bispecifics according to format and composition, distinguishing them according to the presence or absence of an Fc region and a symmetric or an asymmetric architecture. They then further divide bispecifics with an Fc into those with an IgG-like structure and those that contain additional binding sites (i.e. appended or modified Ig-like structure).

This architectural lens is especially helpful given that most of the nomenclature challenges lie within the multispecific antibody space, where formats proliferate rapidly.

However, bispecific and multispecifics are not the only antibody categories with alternative formats. Monospecific antibodies can be assembled using building block-like strategies too, allowing optimization of valency and size. Furthermore, therapeutic antibodies, mono- or multispecific, can be conjugated to molecules (e.g. cytotoxic drugs, radioisotopes, PEG) or fused to non-antibody protein domains (e.g. cytokines, toxins, receptors).5

In a thorough systematic review, Wilkinson and Hale analyzed over 700 therapeutic antibodies with International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) and classified them in 57 antibody-related formats based on their domain assembly. These were grouped into five broad categories: monospecific antibodies, multispecific antibodies, Fc fusion proteins, antibody fusion proteins, and miscellaneous. They also highlighted the increase in complexity of therapeutic antibody design and number of formats, which continue to accelerate from early 2000s, moving away from classic IgGs.2

While these classification systems are informative and able to group antibodies into general format categories, others have gone a step further by proposing actual naming languages for antibody formats. These systems draw inspiration from established molecular notation frameworks such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) for organic molecules and HELM (Hierarchical Editing Language for Macromolecules) for biologics, aiming to provide more tailored solutions for complex biologics.

SMILES has become a widely adopted standard for describing small molecules, though its application to biologics is limited.6 HELM, introduced in 2012 by the Pistoia Alliance, was designed to represent a broad range of complex biomolecules, including antibodies.7 However, while powerful, HELM is not ideally suited for multispecific antibodies due to its complexity, lack of support for annotating Fv specificities, and limited flexibility in representing fused domains.6

To address the unique challenges of next-generation antibody formats, two dedicated systems have emerged:

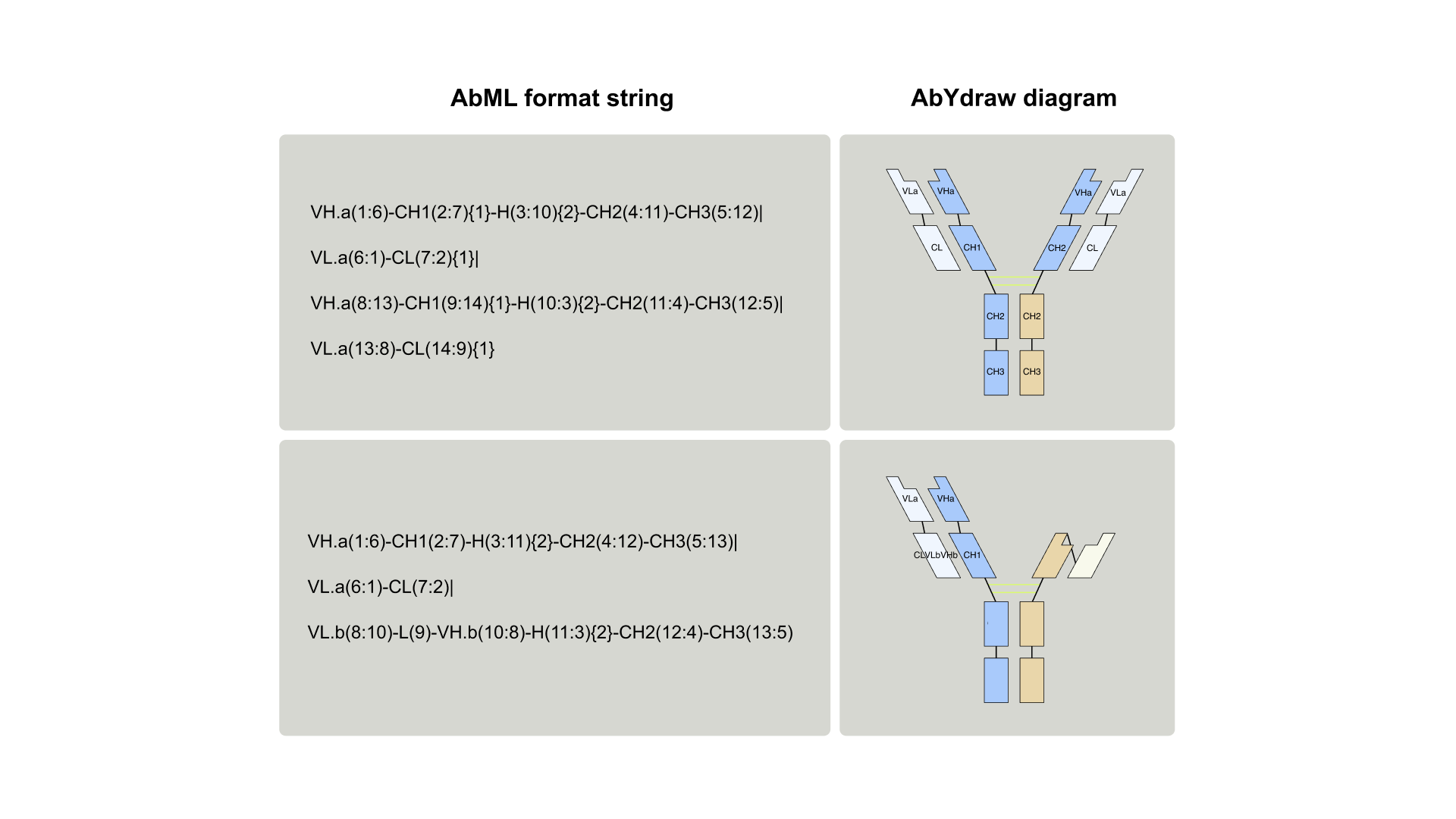

- Antibody Markup Language (AbML), a machine-readable format annotation system 6

- Verified Taxonomy for Antibodies (VERITAS), a human-readable descriptive naming scheme 8

Both aim to provide a standardized framework to communicate structural information about antibody therapeutics, paving the way for better collaboration, database integration, and even AI-assisted drug development.

AbML (Antibody Markup Language)

AbML is a notation language for antibody formats. The language consists in describing antibody domains arranged in a string and separated by connectors. Software (abYdraw) is also provided. This can both generate and render AbML, converting the rather complex-looking notation into visual representations.6

AbML – How It Works

Pros

- Very thorough notation language for antibody formats which allows to annotate fine details with precision.

- Software to generate and render AbML is provided, facilitating a standardized annotation and generation of custom antibody diagrams.

- Future proofed- suitable for annotating all current and currently conceivable antibody therapeutic formats.

- Suitable for thoroughly annotating antibody therapeutic formats as required in patent applications and for international regulatory purposes, including INN applications.

Cons

- Although AbML supports drug conjugation (random or site-specific), these are not currently rendered or supported in abYdraw.

- The notation system produces rather complex strings and is therefore not suitable for use for common scientific discourse, or for grouping formats for computational analysis.

Verified Taxonomy for Antibodies (VERITAS)

VERITAS is a human-readable and standardized nomenclature system designed for multimeric antibody-based formats, relaying structural information about a format in a concise manner, without the need for diagrams. The system is based on the idea that formats can be broken down into various modules and format names are built around a main multimerization center, with N- and C-terminal appendages systematically described following specific rules.8

![Three antibody structures with their various literature names compared to standardized VERITAS nomenclature. Left: Fab-scFv fusion (previously called XmAb®, scFv-Fab IgG, scFv-Fab-Fc, Fab-scFv-Fc, Fab-Fc/scFv-Fc, Fab-scFv-Fc(kih)) standardized as VERITAS '[Fab*scFv]-heteroFc'. Center: IgG with C-terminal scFv fusions (previously IgG(H)-scFv2, IgG-(scFv), IgG-scFv, IgG-HC-scFv, scFv-IgG) standardized as VERITAS 'IgG-scFv'. Right: scFv-Fc heterodimer (previously scFv-KIH, scFv-kih-Fc, scFv-Fc/scFv-Fc, scFv-Fc(kih), scFv-Fc) standardized as VERITAS 'scFv-heteroFc'. Adapted from VERITAS nomenclature system with citations to multiple source publications](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/628cfd01406f3f5bb9c8477d/696f82bac000c2c1589bbcc0_Figure4_blogpost_nomenclature.png)

VERITAS – How It Works

Pros

- Suitable for use in conversations, databases, clinical trial registries, research and patent literature, as well as generic name to use in regulatory documents and INN application documents.

- Suitable for standardizing antibody therapeutic format in new and historical data – to be used for analyses on trends and success rates and as inputs to machine learning algorithms.

- Future proofed- suitable for annotating all current and currently conceivable multimeric antibody therapeutic formats.

- Customizable: flexibility to include or omit information about specificity, valency, and point mutations.

- Relays the structural information in a concise manner without the need for a diagram – important for improving accessibility (suitable as alternative text for schematics representing the structure of the antibody).

Cons

- Format annotation rules for molecules without a multimerization centre not yet described (antibody fragments like scFv, diabodies, scFab, VHH, VH, VL and combinations of these).

- Format annotation rules for Antibody Drug Conjugates not yet described.

Despite the growing complexity of therapeutic antibody formats, the scientific community has yet to adopt a universal system for their classification and naming. AbML and VERITAS represent two promising and complementary approaches to addressing this gap.

AbML offers a precise and detailed syntax ideal for annotating fine structural features and is associated with the abYdraw software for antibody diagrams generation, making it especially suited for regulatory submissions, patent filings, and antibody schematics generation. VERITAS, on the other hand, emphasizes human readability and inclusion of structural information in the name, which makes it better suited for scientific communication, data analysis, and accessibility. While VERITAS currently focuses on multimeric antibody formats, its framework could be expanded to include fragments and conjugates, completing its utility across the full range of therapeutic designs.

Rather than being competing systems, AbML and VERITAS can serve different, and often complementary, purposes. A combined or interoperable approach may offer the best of both: the technical rigor of AbML alongside the clear and concise structural information of VERITAS.

While naming frameworks continue to evolve, teams still need robust internal systems to consistently capture, organize, and interpret the growing diversity of antibody formats. As the industry continues to struggle with the lack of a universal antibody therapeutic nomenclature, Benchling is building the infrastructure that helps teams impose clarity and consistency on an increasingly complex space. Benchling Biologics unifies biologics discovery end-to-end, connecting sequence, functional, and predictive data so teams can design, register, and analyze diverse antibody formats with shared context. Today, tools like PipeBio and Benchling Research already streamline hit identification, in-silico design, and experimental capture within one connected design–make–test–learn (DMTL) loop. And with this year’s Biologics Registry, introducing an antibody-aware data model, custom formats, and intelligent registration tools, scientists will be able to register antibodies of any format, assemble ordered domains into chains, and capture domain-level metadata for richer analysis and AI-readiness, all using a consistent Benchling annotation framework. Together, these capabilities help standardize how teams describe, organize, and work with modern antibody therapeutics, even in the absence of a universal naming system.